COVID-19 is having a strong impact on the world economy and there is still great uncertainty on how the industry can recover from this downturn.

However, looking back on the great crisis of the past, such as the crisis of 2008 or the great depression in 1929, one can see that these times of great turmoil also provided significant technological breakthroughs.

So, can the business practices of the 1930s yield useful lessons for executives setting priorities in today’s uncertain and evolving environment?

Based on the outcomes of many investments promoting innovation, the answer appears to be affirmative. Patent applications by companies with R&D laboratories were considerably lower during the 1930s than in the preceding decade.

So, patent applications were more synchronized with the business cycle during the Depression, when the cycle was extremely volatile, than they had been during the ’20s when economic conditions were buoyant.

However, several successful companies did not delay such investments. One was DuPont that in 1930 recorded the discovery of neoprene. These advancements were pursued even though the sales of the company fell by roughly 10 and 15 percent. Neoprene was to be commercially available in 1937 and two years later was disseminated in the automotive and aeronautical industries.

Photo: Wallace Carothers, inventor, and leader of DuPont

Similarly, DuPont discovered nylon in 1934 and introduced it in 1938 after intensive R&D and product development [1]. Hewlett-Packard and Polaroid were also established as entrepreneurial start-ups during the 1930s.

The experience of the 1930s also illustrates that although deep downturns are destructive, they can also have an upside. Joseph Schumpeter emphasized the positive consequences of downturns, specifically through the destruction of underperforming companies, the release of capital from dying sectors to new industries, and the movement of high-quality, skilled workers toward stronger employers [2].

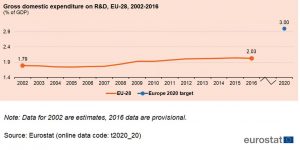

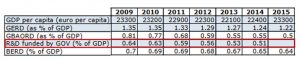

In 2008, a similar trend was observed, but this time Europe saw a general increase in R&D spending that propelled it to a more speedy recovery. This was more evident in strong economies with innovation sectors such as Germany, Denmark, and the United Kingdom where R&D funding levels remained robust in both the public and private sectors. Germany, for example, increased its public funding by 46% since 2008, from US$23 billion to $34 billion in 2016.

Based on Booz & Company’s (today’s “Strategy&” of PwC) “Global Innovation 1000“ survey of the largest R&D spenders showed an innovation investment growth rate of 5.7% in 2008, even though net incomes plummeted by 34%.

More than 9 in 10 executives participating in the survey said that innovation was critical to growth for the upturn. Only 21% of these companies reduced the size of the R&D portfolio in 2008, while over 70% of the firms focused on the growth potential investing in the development of more products for both new and existing markets.

However, in southern European countries hit hardest by the recession, such as Greece, Spain [3], and Portugal [4], R&D funding from the government plummeted when compared with the early 2000s. As an example, Spain’s public funding dropped by 25% between 2009 and 2016, from $9.6 billion to $7.1 billion.

Photo: Informe Nacional Rio 2016: España [ 5 ]

So what solutions are there when companies have fewer funds available to them?

While bigger companies may opt to internalize their R&D departments, Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have to consider the option of collaborating with R&D driven companies and startups through an open innovation platform.

Open innovation assumes that firms can and should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, and internal as well as external paths to market, as they look to advance their innovations [6].

Often, SME’s only look to collaborate when a specific customer request pushes them beyond their own competence area. Yet, startups mention that collaborations constitute an integral part of their strategy [7]. Considering the need for aggressive innovation on the part of SME’s and the willingness for startups to collaborate, it seems evident that there are evident gains for both parties through the collaborative development of innovative solutions.

Another available strategy is to outsource the R&D activities to a trusted partner such as Academia or Research and Technology Organisations (RTOs).

An outsourced partner can offer a unique, niche expertise for product or process development needs and ensure internal technology transfer and scientific and technic knowledge absorption and dissemination. Also, an outsourced R&D partner will meet temporary development needs without imposing a long-term commitment. This approach allows controlling of costs throughout the recession while maintaining a competitive edge in the market.

Photo: PIEP – Innovation in Polymer Engineering, Portuguese RTO

A number of important EU policy strategies and initiatives address such win-win situations and help to implement the three main goals for EU research and innovation policy, which can be summarised as Open Innovation, Open Science and Open to the World. The follow-up program Horizon Europe will continue to promote R&D at the intersection of disciplines, sectors, and policies over the period 2021 to 2027, with a proposed budget of EUR 100 billion [8].

And while national and regional programs are in place to foster technological developments, SME’s can always run shorter, more contained private R&D projects to gradually increase their knowledge of key strategic technologies, positioning themselves for the new upcoming markets.

Author: Pedro Mimoso, Business Development Director at PIEP

[1] T. Nicholas, “Innovation lessons from the 1930s,” The McKinsey Quarterly, 2008.

[2] C. H. Matthews and R. Brueggemann, Innovation and Entrepreneurship: A Competency Framework. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2015.

[3] J. Rehm, “Ten years after the economic crash, R&D funding is better than ever,” Nature, Sep. 2018.

[4] A. Margarida, N. Moreira Da Silva, S. M. Tavares, S. Anabela, and J. M. Carneiro, “The Determinants of Participation in R&D Subsidy Programmes: Evidence from Firms and S&T Organisations in Portugal,” Faculdade de Economia da Universidade do Porto, 2014.

[5] A. Fernández-Zubieta, I. Ramos-Vielba, and T. Zacharewicz, “Informe Nacional RIO 2016: ESPAÑA,” Sevilla, 2017.

[6] M. Bogers, H. Chesbrough, and C. Moedas, “Open Innovation: Research, Practices, and Policies,” Calif. Manage. Rev., vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 5–16, Feb. 2018.

[7] “Innovation by Collaboration between Startups and SMEs in Switzerland,” Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev., vol. 7, no. 12, 2017.

[8] Eurostat, “Europe 2020 indicators-R&D and innovation Statistics Explained General overview,” Jun. 2020.